Policy considerations for financing CGT

Precision Financing Solutions require implementation in accordance with various governmental regulations. The Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (MDRP) only recently provided regulations to address such contracts but did not resolve all related issues.

FoCUS has identified six key federal policy issues with policy recommendations, listed in priority order below. The most critical issue remains Medicaid Best Price benchmarking with performance-based agreements.

The table below highlights outstanding policy concerns to consider for each of the Precision Financing Solutions. Policy support is required to remove existing inadvertent barriers to these arrangements and to proactively facilitate broader utilization of innovative payment models. The importance of these policy changes corresponds to the number of checkmarks.

|

Enabling change |

Milestone-based contract |

Multi-year milestone-based contract |

Performance-based annuity |

Payment over time/installment financing |

Warranty |

|

Address Medicaid Drug Rebate Program rules for AMP and ASP calculation and VBC Medicaid participation challenges. |

✓✓✓ |

✓✓✓ |

✓✓✓ |

✓✓✓ |

✓✓✓ |

|

Update Anti-Kickback Statute safe harbor inclusion. |

✓✓ |

✓✓ |

✓✓ |

✓✓ |

✓✓ |

|

Address FDA manufacturer communication guidelines for early discussion and use of outcome metrics not found in the label. |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Revise HIPAA to ease collection of patient outcomes and insurer status data collection. |

✓ |

✓✓ |

✓✓ |

✓ |

✓✓ |

|

Allow for state and federal regulations to permit deductible and co-pay waivers. |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Provide for fair provider payments. |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

MDRP and Innovative payment models

The CMS MDRP rule on value-based purchasing (VBP) arrangements has broadly addressed previous policy concerns for several innovative Precision Financing Solutions: milestone-based contracts, multi-year milestone-based contracts, performance-based annuity, and installment payments (see sidebar). Other models such as subscription models remain effectively impractical without legislation or creative rulemaking to reform the unit price reporting and their impact on Average Manufacturer Price.

The enabled innovative payment models may still be impeded from adoption due to:

- Ambiguity regarding reportable VBP design variations, as current policy bolsters standardization rather than customization to each commercial payer’s needs.

- Reduced provider 340B margins caused by the inclusion of VBPs in ASP calculations;

- ASP volatility, which has the potential to trigger inflation rebates from inclusion of VBPs in ASP calculations.

See this research brief for additional insights into the relationship between the CMS rule on VBP arrangements, Medicaid Best Price, AMP, ASP, and 340B pricing.

MDRP pricing policies

The Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (MDRP) was created in 1990 to help offset state and federal costs for outpatient prescription drugs. For covered outpatient drugs, Medicaid receives a “Unit Rebate” on every unit purchased for Medicaid patients. This rebate is either a percentage of Average Manufacturer Price (AMP) (23.1% for most branded products, 17.1% for pediatric drugs and clotting factors and 13% for generics) or the best price available to any commercial buyer. When the program was established, MDRP did not anticipate payment-over-time arrangements or value-based contracts where the outcome-based rebate for a single commercial patient could end up setting the best price for ALL Medicaid patients using that drug.

In December 2020, CMS modified the MDRP regulation to address the need for innovative payment arrangements such as value-based purchasing (VBP) for drug therapies and pay-over-time. The updated MDRP rule, which went into effect July 2022, excludes commercial drug sales under a VBP arrangement from the calculation of the AMP; best price only considers sales outside of the VBP arrangement, thus eliminating the ‘single patient’ risk. CMS regulations further require developers to offer the VBP arrangement to all state Medicaid programs. States can elect whether to receive Medicaid rebates based on the standard rebate terms or participate in the VBP arrangement.

CMS regulations outline VBP models using either a multiple best price or a bundled sales approach. Currently, states that want to take advantage of a VBP arrangement must contact the developer to enter into an agreement. Once the agreement is in place, the state must manage the determination of outcomes and invoice the developer for any rebates owed. Beginning in 2025, states will have the option to assign CMS to structure and coordinate multi-state VBP agreements, also termed as Outcomes Based Agreements (OBAs).

The updated MDRP regulation also addressed pay-over-time arrangements. Developers should report the full price of the drug in the quarter in which the drug was sold, regardless of the payment arrangements negotiated with payers.

Ambiguity regarding reportable VBP variations leads to standardization of contract terms –The new MDRP CMS rule requires VBP arrangements to be offered to all states through entry into the Medicaid Drug Program system. The rule does not describe the types or degree of customization that triggers classification as an alternative VBP design. Given the administrative complexity of offering multiple VBPs for a product, developers are likely to offer only one, take-it-or-leave-it tiered design for all payers. The CGT Access Model1 will test voluntary multi-state outcomes-based agreements between manufacturers and state Medicaid programs with the goal of increasing access to CGTs beginning in 2025. It is likely the model will further advance standardization and lessen innovation and customization for specific payer needs. Importantly, this single take-it-or-leave-it design may also reduce price competition among commercial payers that in turn may restrain the economic benefits to Medicaid.

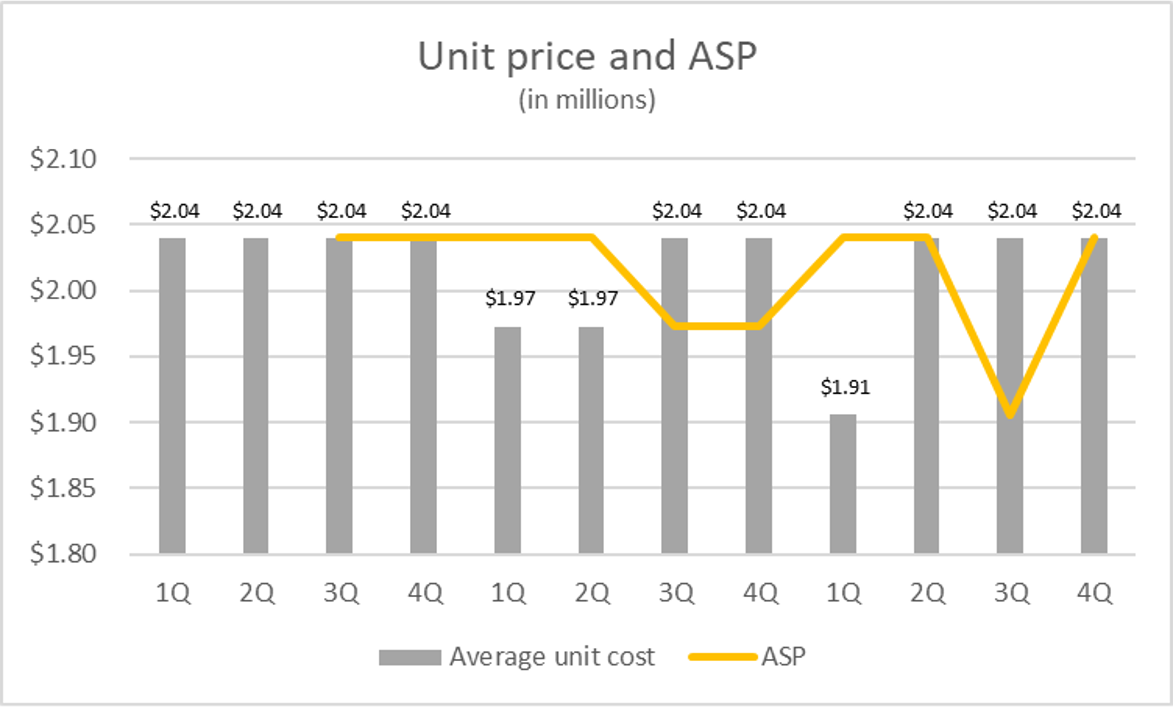

Reduced provider 340B margins caused by the inclusion of VBPs in ASP calculation – To avoid inappropriately setting a national Medicaid rebate based upon a single patient with a large performance-based rebate, the new MDRP VBP arrangement for drug therapy rule excludes VBPs from the calculation of Average Manufacturer Price (AMP). However, the ASP calculation includes price concessions for VBPs in its computation, along with volume discounts, prompt pay discounts, cash discounts, free goods, chargeback rebates, and any other price reduction arrangements.2 Under current Federal regulations, manufacturers apply rebates to quarterly sales in the quarter they are realized, forgoing retrospective price adjustments. The ASP price for a product is set from the average unit price of sales from two quarters prior. Figure 1 illustrates the impact of VBP rebates in the calculation of a product’s ASP in one fictional scenario.

ASP is commonly the basis for provider reimbursement, as CMS sets provider payments at ASP + 6%. In Figure 1, reimbursement per unit based on ASP +6% in Q2 of year two would be $2,162,000 but would drop to $2,088,000 in Q3 and Q4 before returning to $2,162,000. Reimbursement in Q3 of year three would decrease to $2,024,000.

Figure 1. ASP Illustrative case with a VBP contract (VBC)

Illustrative account of a rare condition gene therapy in which 25 patients are treated per quarter. Ten units per quarter are sold at $2.1M under a VBC and 15 units per quarter are sold at $2M with no VBC. The terms of the VBC provide a rebate of 80% of drug costs for treatment failures. A single failure occurs in each of the first two quarters of year 2. There are two occurrences of failure in Quarter 1 of year 3. ASP values for the VBC rebates lag unit costs by two quarters.

Providers would be challenged to adjust to $74,000 – $138,000 less revenue per unit for quarters. Moreover, ASP values that include performance rebates do not change the purchasing price of the product. The table below illustrates reimbursement scenarios where the purchase price of a product based on our illustrative case is less than the product’s price.

|

No rebate ASP (millions) |

One rebate payout (millions) |

Two rebate payouts (millions) |

|

|

ASP |

$2.04 |

$1.97 |

$1.91 |

|

Profit - $2M purchase price |

$0.16 |

$0.09 |

$0.02 |

|

Profit - $2.1M purchase price |

$0.06 |

($0.01) |

($0.08) |

Such financial reductions in profit margin, including scenarios of costs exceeding reimbursement, may result in a delay in patient treatment or consideration of other therapy options with higher provider margins that do not use VBPs. Thus, the ASP effect disincentivizes developers from offering value-based contracts.

ASP volatility can trigger inflation rebates – Drug developers face a different challenge with ASP volatility. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 requires drug manufacturers to pay a rebate to the federal government if prices for single-source drugs and biologicals covered under Medicare Part B and nearly all covered drugs under Part D increase faster than the rate of inflation (CPI-U). In this policy, price changes are measured based on ASP for Part B drugs and AMP for Part D drugs. Medicaid has a similar inflation provision based on AMP. Sales of products covered by VBCs are excluded from AMP calculations. However, ASP will include performance-based rebates, potentially generating additional rebates when ASP changes are greater than the growth of CPI-U. ASP changes are 3.4% and 7.4% for the scenarios in the above Figure, potentially resulting in additional rebates if CPI-U growth is less than 3.4% or 7.4% at the time of those changes. ASP volatility exposes developers to additional rebate payments without realizing increases in revenue, thereby decreasing the desirability to engage in VBP for drug therapies.

Recommendations/suggestions:

- To address ambiguity regarding reportable VBP variations and operational barriers, we encourage CMS to explore the following:

- Provide technical guidance that would describe the types or degrees of customization that trigger classification as an alternative VBP design. For example, is it an alternative VBP design if rebate values are modified, or outcome criteria are defined with a slight difference?

- Facilitate scaled-up CMS grants to state Medicaid agencies to develop the capabilities and resources to design, negotiate, and implement these agreements. FoCUS experience suggests that there is a meaningful learning curve in establishing these types of VBP arrangements. Grants to date have enabled some capacity for VBP arrangements: multiple states have used CMS’s State Innovation Model (SIM) program grants to make strategic investments in HIT infrastructure to improve EHR interoperability, connect more providers to HIEs, and boost aggregation of data across payers and providers. More grants will be required to scale up these efforts.

- Collaborate with all stakeholders to advance the design of a CGT Access Model to promote optimal success of value-based purchasing for all. Consider existing interstate purchasing pools, which currently provide administrative support to states, to administer VBP arrangements as well.

- Consider options to simplify the process for states to obtain CMS approvals to enable adoption of Precision Financing Solutions. It would be helpful if CMS could clarify whether the agency’s expectation is that each state seek a State Plan Amendment (SPA) to take advantage of the relevant VBP provisions being proposed. To do this, the agency could consider offering a blanket approval rather than requiring individual SPAs, or issuing a pre-approved SPA template that states could adopt akin to ‘automatic approval.’

- Advance efforts to track outcomes for performance-guarantees. FoCUS experience suggests that states will require resources to track and extract data to evaluate performance in outcomes-based contracts. CMS may be able to help advance real-world data systems capable of national longitudinal patient monitoring. For example, CMS could allow the IT investments needed for performance tracking as part of capability grants; facilitate cross-disease area and cross-sectoral collaborations to create scale in data collection; enable cross-state/cross-payer interoperability; and link patient movement across payers. FoCUS recommends utilizing developers’ knowledge of patient data sources. It is also imperative to define data element standards to ensure data uniformity and to maintain data interoperability.

- To address ASP volatility, we recommend legislative changes. The House Ways and Means Committee sent legislation (HR 2666) for consideration to the House to address ASP volatility for providers and developers in May 2023. FoCUS recommends continued emphasis on the guidance to exclude VBC rebates from the calculation of ASP.

Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS) to define explicit safe harbor

Issue: The AKS regulations currently provide a safe harbor for traditional rebates, but do not explicitly include value-based agreements that tie payments or rebates to outcomes and may pay for monitoring visits that relate to the terms of the value-based agreement.

Recommendation/suggestion: Explicitly include rebates and payments arising from performance-based agreements in an AKS safe harbor.

FDA communication guidelines to enable appropriate performance metrics

Issue: Payer agreements that use performance metrics not reported in the FDA-approved label may place the developer in violation of FDA guidelines for communication with payers.

Recommendation/suggestion: FDA should clarify that patient real-world performance metrics are acceptable in performance-based agreements when therapies are administered to patients in accordance with the label indications and usage criteria. Metrics should not be limited to those included in the FDA label. FDA guidelines remain relevant for any communications regarding metrics.

HIPAA to enable patient data visibility to all involved parties

Issue: Sharing patient performance data among the involved parties in performance-based agreements (especially developers and subsequent payers) often requires additional hurdles due to Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations that did not contemplate this type of agreement.

Recommendation/suggestion: The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) should amend HIPAA regulations to ensure that those investing in patient health through long-term performance-based agreements can access needed, relevant data. HHS should also clarify any enabling requirements for patient and provider consent forms.

Federal and state insurance regulation to allow deductible and co-pay waivers

Issue: Federal and state insurance regulations usually require payers to refile and approve insurance products if they alter patient benefit designs. This 12–18-month process can delay patient-favorable changes by payers.

Recommendation/suggestion: Amend regulations to allow payers to make modifications beneficial to all participants – such as reductions or waivers of deductibles, co-pays, and coinsurance payments; increases in patient incentives; and other improvements in patient access for specific therapies—with automatic regulatory approval upon filing with insurance regulators.

Fair provider payments

Issues: Some therapies provided in the inpatient setting are reimbursed by Medicare through existing fixed-rate bundled payments (e.g., DRGs) based on patient diagnosis that are intended to cover a range of possible treatment options as part of single inpatient admission. New high-cost therapies in this setting can create a substantial loss for providers if they choose to use such a therapy. This challenge persists despite potential new technology add-on payments that seek to account for the cost of the therapy not yet included in the DRG payment amount. Thus, providers are concerned that reimbursement will continue to be a barrier to access for Medicare patients.

In the outpatient setting, payment rates are more predictable than in the inpatient setting. Medicare typically pays the Average Sales Price (ASP) plus 6% for separately-billable drugs. In a recent ruling, beginning in calendar year 2023, CMS will also pay for all outpatient drugs purchased under 340B using the same formula. This essentially removes disparate treatment from prior distinctions of pass-through versus non-pass-through drugs. However, unlike Medicaid Best Price and AMP, the calculation of ASP includes value-based contract rebates. This may lead to significant volatility in the value of ASP and, therefore, provider payments. See the MDRP and innovative payment models (links to above section) section for more information.

Recommendation/suggestion: Policymakers should ensure predictable payment that equalizes reimbursement levels across settings of care. CMS should establish fair and predictable payments to ensure appropriate provider reimbursement in all settings. Policymakers should also promote legislation to exclude VBC sales from the calculation of ASP.

Policy actions for enabling Precision Financing Solutions

Medicaid Best Price Volatility Could Inhibit Payment Innovation

Incorporation of Value-Based Payment Agreements into the Calculation of Medicaid Drug Rebates

Federal Communication Guidelines

State Insurance Regulations Regarding Benefit Design (Deductible and Co-Pay Waivers)